Blog

"Guest Lecturing at NTU: Lessons on Mentorship and Communication"

On August 24, 2025, I had the opportunity to guest lecture and teach virtually through Google Meet for Psychology and Communication: Applications in Health and Behavioral Sciences at National Taiwan University. My session focused on fostering mentoring relationships for professional development, with a particular lens on letters of recommendation.

At its heart, the talk was about one idea: mentorship is not transactional. It is relational. Recommendation letters may be the visible outcome, but the real work is in the connection that develops long before a deadline arrives.

Why Relationships Matter

I began by naming a common mistake: contacting a mentor only when you need something, like a letter. If you do this, the letter might get written, but it will likely be ineffective, because the mentor doesn’t have recent examples of your growth, your contributions, or your goals.

Stronger letters come from mentors who have seen your development over time. They can speak not just to your grades or your CV, but to how you’ve handled challenges, supported others, or grown as a professional. Those details only emerge when a relationship has been nurtured along the way.

For me, the foundation of these relationships comes down to three qualities: curiosity, consistency, and follow-through.

- Curiosity: showing genuine interest in your mentor’s work and perspective.

- Consistency: checking in and sharing updates, even when you don’t “need” something.

- Follow-through: keeping your word, updating them on outcomes, and closing the loop.

Cross-Cultural Considerations

Because this course was taught in Taiwan, I acknowledged something I had learned in conversation with the teaching assistant, Ryan: many Taiwanese students feel hesitant to ask professors directly, out of fear of overstepping or burdening them.

This contrasts with U.S. settings, where direct requests are not only typical but expected. Professors often see clear, specific asks as a sign of respect and initiative.

Neither approach is wrong. What matters is aligning your communication style with your context, while remembering that the principles of respect, clarity, and preparation are universal.

Communicating Effectively

Once you’ve built the relationship, the way you communicate can either strengthen or weaken your request. Clear, respectful communication shows consideration for your mentor’s time and makes it easier for them to help you.

Some students might see these steps as “extra work.” But I reframed it this way: preparing a clear request is not unnecessary work; it is relational work. It is a form of consideration for your mentor and for yourself. Most people will not go out of their way to help without first seeing that kind of consideration.

There are no guarantees. A professor may still decline. But taking the time to ask thoughtfully, to prepare thoroughly, and to give them an easy way to say no, that’s what builds trust over time.

Intent and Impact

In the lecture, I reminded students that what matters most in communication isn’t writing a “perfect” message, it’s making sure your intent is clear. When intent isn’t communicated, the impact can feel very different from what you meant.

That’s why I encouraged students to pause and ask themselves: “What’s my intent here, and how clearly am I communicating it?”

Clarity and consideration are what turn a simple request into an opportunity to strengthen the mentoring relationship.

Student Response

During the Q&A, one student commented that they appreciated my focus on avoiding transactional relationships. That affirmation meant a lot. At the same time, I sensed that some of the step-by-step communication guidance felt redundant to them.

That tension is real. Sometimes teaching means surfacing the “obvious”, so that when stress or deadlines come, students can rely on those basics. What feels simple in the classroom is often the first thing forgotten in real life.

Reflections on Teaching

I only realized at the end that students had to use a mic to ask questions. That explained why the session felt more like a structured lecture than an interactive seminar. I had presented virtually in Milan a few years ago with the same format, and it supported a strong didactic delivery.

The tradeoff was that interaction happened mostly during the Q&A instead of throughout the talk. That set-up worked well for focused teaching followed by thoughtful student reflections. The message still came through clearly: mentoring grows through respect, reciprocity, and trust, whether shared in person or across a screen.

Closing

I am grateful to Dr. Michi Fu, Ryan, and the NTU students for the invitation and the conversation. Whether you are in Taipei, Los Angeles, or anywhere else, the reminder holds: the strongest mentoring relationships grow not from transactions, but from curiosity, consistency, and considerate communication.

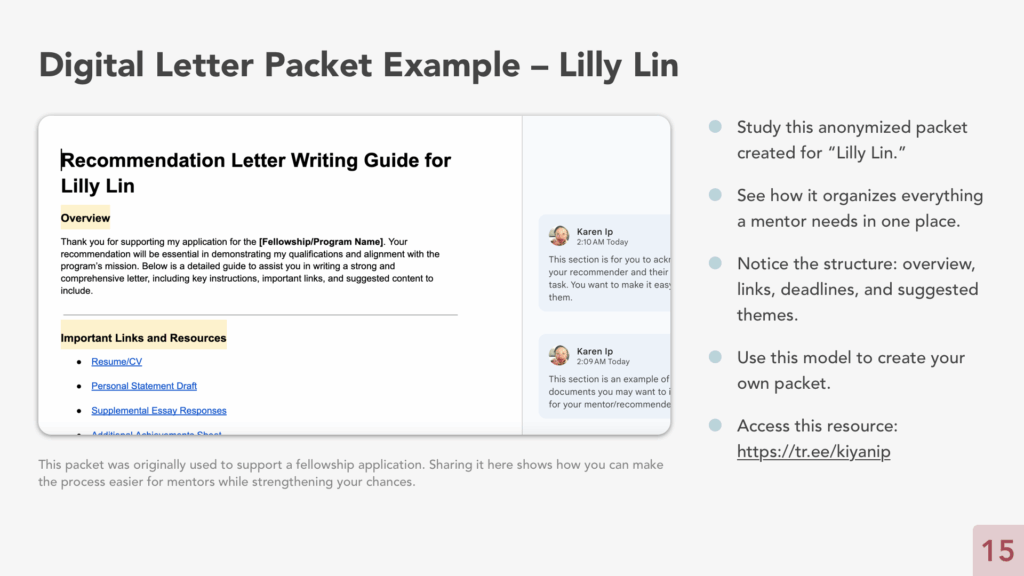

For those interested, I’ve also made the slides and resources available here: Linktree.